What Happened to Sifteo Cubes?

An ambitious toy born at MIT, Sifteo Cubes mixed screens and sensors to reinvent play. They vanished quickly, but a passionate community and a few spiritual successors keep the idea alive.

Technological innovation in toys has produced its fair share of success stories, from talking dolls to game-enhanced figurines. As sensors, wireless chips, and small LCDs became increasingly affordable in the early 2010s, a new class of toys emerged that blended physical interaction with digital feedback. Among these was Sifteo Cubes, a bold experiment in merging play, education, and spatial reasoning. Where others, like Skylanders, used technology to bring physical toys into video games, Sifteo flipped the formula by bringing the logic of games into tangible, interactive cubes.

Each Sifteo Cube was a small screen packed with sensors, designed to respond to movement and proximity. Games weren’t just played on the cubes. They were played with them by tilting, sliding, and aligning them in space. It was a compelling idea, both technically and creatively.

The following sections explore what made Sifteo Cubes so special, why they struggled in the market, and how their legacy is quietly being kept alive.

Origins

The story of Sifteo Cubes begins at the MIT Media Lab, where researchers David Merrill and Jeevan Kalanithi explored the idea of tangible user interfaces. Their project, dubbed Siftables, introduced a new interaction model: small, screen-equipped tiles that could sense their position, orientation, and neighbors. Instead of navigating through digital content with a keyboard or touchscreen, users could physically manipulate these intelligent tiles, turning abstract computation into something more hands-on and intuitive. The concept caught widespread attention after Merrill’s TED Talk in 2009, which showcased how Siftables could be used for math games, storytelling, and even musical composition.

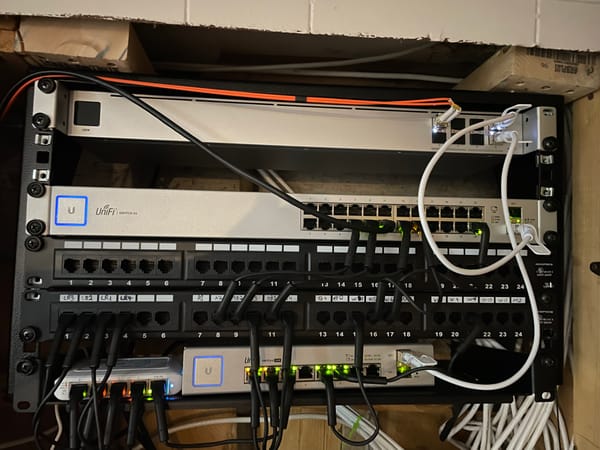

Encouraged by the enthusiastic response, Merrill and Kalanithi spun the project out of MIT and founded Sifteo Inc. Their goal was to bring the concept of Siftables to consumers in the form of a fully realized product. While Siftables had been more of a research prototype, Sifteo Cubes needed to be manufacturable, affordable, and reliable. This meant redesigning the hardware from the ground up, optimizing for battery life, wireless communication, and usability. The result was the first generation of Sifteo Cubes, launched in 2011, followed by a more polished second generation in 2012.

Although Sifteo Inc. secured funding and assembled a team of engineers and game designers, bringing such an unusual product to market was no small feat. They weren’t just creating a toy, they were building an entirely new category. It needed not only clever hardware, but also developer tools, games, distribution channels, and a support ecosystem. For a time, it seemed they might succeed. The cubes impressed at tech expos, garnered praise in educational circles, and stood out in a market saturated with conventional touchscreen devices.

Introducing the Cubes

With Sifteo, games were played by physically manipulating the cubes—tilting, sliding, rotating, and arranging them in space. In a word puzzle, for example, players might align cubes in sequence to form valid words. Other games leaned heavily into the tactile aspect, requiring players to physically reconfigure the cubes to progress. It was a fresh and intuitive way to play—equal parts toy and tech.

Released in 2011, the first generation of Sifteo Cubes were compact, interactive devices measuring roughly 1.5 inches per side. Each cube featured a 128x128 pixel full-color LCD screen, a 3-axis accelerometer, and Sifteo’s proprietary near-field object sensing technology. Internally, the cubes were powered by a 72 MHz STM32 microcontroller based on an ARM Cortex-M3 core, paired with 8MB of flash memory. Communication between cubes used a 2.4GHz wireless radio, and the entire unit was powered by a rechargeable lithium-polymer battery offering about four hours of playtime.

While the inclusion of a full ARM processor in each cube allowed for impressive autonomy and responsiveness, it also came at a cost. Every component—battery, memory, power regulation—added to the bill of materials, and each dollar spent on the CPU translated into several more once manufacturing, assembly, and retail markup were factored in. This architecture was powerful but expensive, and it contributed significantly to the high retail price of the platform.

Second Gen

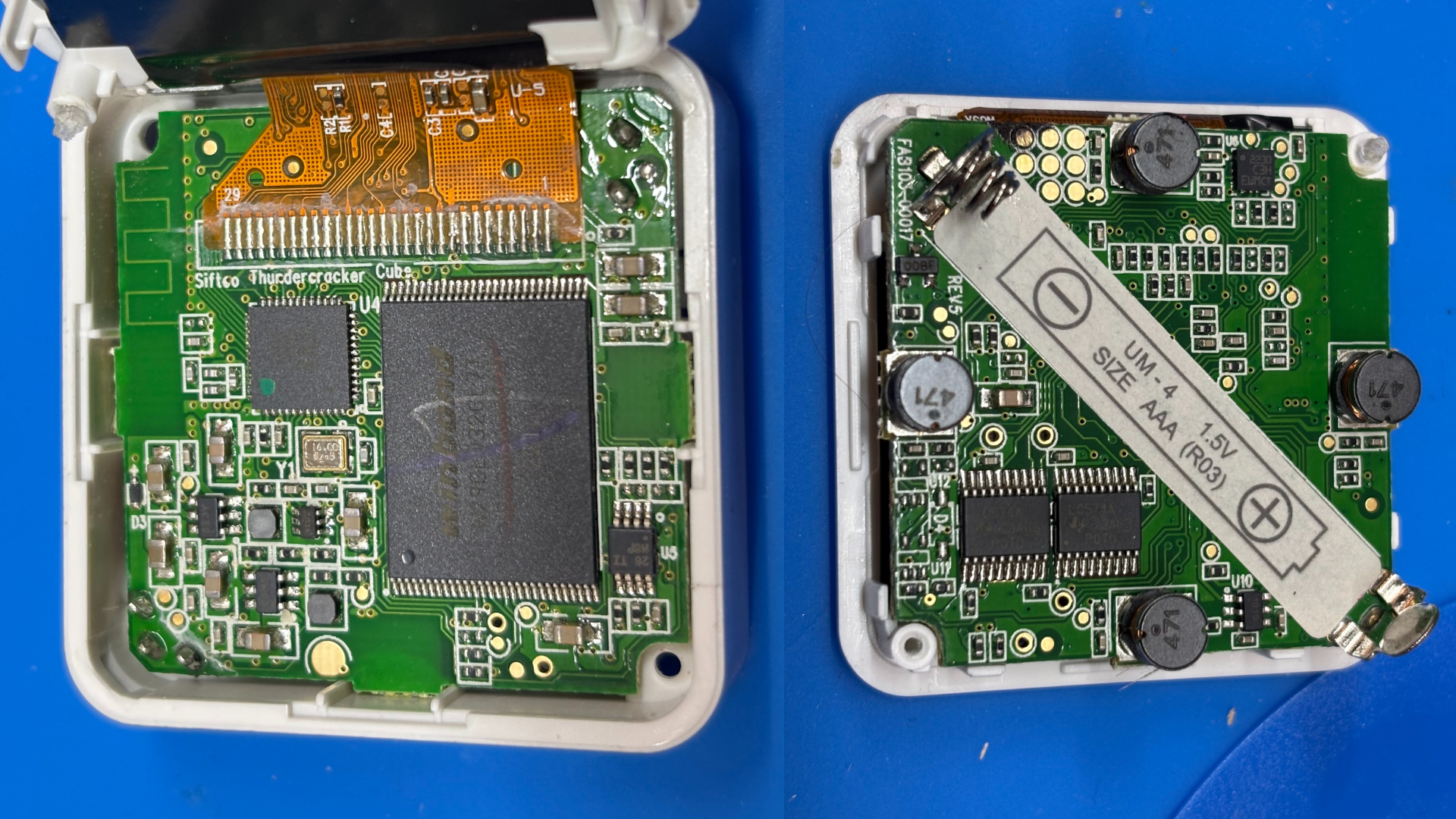

In 2012, a second-generation of Sifteo Cubes, codenamed Thundercracker, was introduced, born from a single goal: reduce the cubes to their essential components and eliminate unnecessary complexity. The result was a clever redesign that moved the CPU and many of the more expensive components into a centralized base unit called the bridge. Each cube now functioned more like a remote GPU, offloading game logic to the bridge while remaining responsive and interactive. This architecture still ran on an ARM STM32F105 chip at the core, but with much leaner demands placed on each individual cube.

This new design was made possible in part by the Nordic nRF24LE1, a compact chip that included a 16 MHz 8-bit microcontroller, 16 kB of program memory, 1 kB of RAM, and built-in wireless connectivity. It handled LCD updates and communication with the bridge, allowing the cubes to behave like lightweight display terminals.

However, the bridge's microcontroller wasn’t powerful enough to drive dynamic gameplay on its own. To solve this, Sifteo engineers turned to a sprite-based rendering engine inspired by retro game consoles like the Game Boy Advance. Graphics and background data were preloaded into onboard the cube's WinBond W29GL flash chips, and the bridge simply transmitted commands telling each cube which sprites to display and how to position them.

Beyond architectural changes, the updated cubes introduced practical hardware improvements. Capacitive touchscreens replaced clicky displays, support expanded to up to 12 cubes per system, and the move to user-replaceable AAA batteries made them far easier to maintain. These changes made the second generation more scalable, more robust, and yet cheaper to produce.

Developing the Brand

Sifteo’s biggest challenge wasn’t the technology. It was visibility. Outside of tech conferences, niche blogs, and a few educational features, the cubes received little mainstream exposure. There were no major ad campaigns or prominent retail partnerships. Distribution was limited to the company’s website and a few third-party sellers, with frequent stock shortages further dampening momentum. Even when Sifteo tried to raise its profile, such as securing a licensing deal with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, the product never appeared in major toy stores. Unlike Skylanders, which dominated shelves and toy aisles, Sifteo struggled to reach its audience.

Part of the issue may have been confusion around who that audience actually was. The product's price, starting at 120 USD for a basic three-cube set, placed it out of impulse-buy territory for many parents. Adding new games required creating an account, installing desktop software, and entering a credit card. The website used a clean, corporate tone and often showcased adults or teenagers gathered around a table, even though titles like Sandwich Princess were clearly aimed at children. Sifteo was marketed like a gadget but shaped like a toy, caught somewhere between educational tool and entertainment product. Without a clear identity or easy accessibility, it quietly slipped past most consumers entirely.

Acquisition and Shutdown

In 2014, Sifteo was quietly acquired by 3D Robotics, a company focused on consumer and enterprise drones. The acquisition was never heavily publicized, but it marked the end of Sifteo Cubes as a consumer product. Following the deal, Sifteo’s original website was taken down, and no further updates were released for the platform. For existing users, especially those who had invested in the second generation of cubes, this meant no new games, no support, and no clear upgrade path. The ecosystem effectively vanished overnight.

Rather than let the technology disappear entirely, Sifteo released much of its internal tooling and firmware to the public. The codebase, dubbed Thundercracker, included the compiler, SDK, emulator, and firmware used to build games for the second-generation cubes. While not exactly user-friendly, this open-source release gave hobbyists and developers a way to preserve, explore, and even expand the platform. It also marked a rare case where a discontinued toy didn’t just fade into obscurity, but instead left behind a technical legacy for others to build upon.

Revival

Years after the last cube shipped, a quiet but determined effort to resurrect the platform began. This effort did not come from a company or investor, but from within the community itself. In 2020, educator and game designer Dr. Mike Reddy began documenting his attempts to restore a long-forgotten set of second-generation cubes. His blog dives into the process of recovering software tools, exploring the Thundercracker open-source SDK, and addressing the many hardware challenges that come with reviving a discontinued platform.

Finding working hardware was no easy task. Even shortly after Sifteo shut down, the cubes were already difficult to find. Complete kits routinely sold for high prices on eBay, a trend that only worsened over time. First-generation cubes presented an added complication, as they were built with sealed lithium-polymer batteries that could not be replaced easily. Restoring these units often required delicate work or salvaging parts from other broken cubes. Dr. Reddy shared his findings and lessons in a talk at EMF Camp 2022, helping to document not only how the technology worked, but how much effort was needed to bring it back. His work highlighted just how inaccessible the platform had become, and why a modern reinterpretation might be the only viable path forward.

JoysCube

As interest in Sifteo quietly persisted among educators and developers, a new project emerged to carry the concept forward. Joyscube is a modern reimagining of interactive cube-based play, designed to overcome the hardware and accessibility limitations that plagued Sifteo. Developed by a team of engineers in China, the project was launched through Kickstarter and Indiegogo, where it successfully raised funds and shipped hardware to backers. The cubes combine multi-touch displays, wireless communication, and onboard sensors in a modular system built for both entertainment and education. Where Sifteo required base stations and a companion app, Joyscube runs independently and supports Android, Windows, and even VR applications out of the box.

While not officially affiliated with Sifteo, the Joyscube team acknowledged the project’s influence and borrowed tools created by members of the Sifteo community. Dr. Mike Reddy publicly noted that elements of his reverse-engineered Sifteo software were reused without attribution, though the team later sent him hardware and shared some of their own work as a goodwill gesture.

Each cube includes six interactive faces and supports gestures like tilting, shaking, and sliding. Games are launched from a central app and can span up to twelve cubes simultaneously, offering experiences that range from storytelling and logic puzzles to real-time multiplayer games.

The project successfully shipped hardware to backers following its crowdfunding campaigns, and early demos showed promise. However, since 2022, there have been no public updates, software releases, or signs of ongoing development. As it stands, Joyscube may have joined Sifteo in the growing archive of ambitious, short-lived experiments in tangible computing.

Success or Failure

So was Sifteo a success, or was it a failure? From a commercial standpoint, the answer is clear. The product struggled to gain market traction and was ultimately discontinued after a brief run. Yet the idea behind Sifteo Cubes has proven far more resilient than the product itself. The technology captured the imagination of educators, developers, and tinkerers who saw in it a glimpse of what interactive, spatial computing could be.

That vision continues today through community-led efforts. Open-source tools like Thundercracker keep development possible, and projects like Wildflower have extended the creative potential of the platform. Thinkerers, like Jared Wolff who modded the controller to add an audio jack, continue hacking away at the platform, improving it. Most notably, the work of Dr. Mike Reddy has been instrumental in documenting, preserving, and reviving Sifteo hardware and software. Anyone with a working set of cubes, or hoping to bring theirs back to life, should visit his site for invaluable guides, downloads, and installer tools.

Sifteo Cubes may not have changed the toy industry, but they helped redefine what a toy could be. Their influence can be seen in spiritual successors like the WOWCube, a more powerful and modern take on modular, screen-based play. As the definition of interactive entertainment continues to evolve, Sifteo’s legacy lives on in the hands of those still curious enough to explore it.

2025-05-18 : Article updated to reflect all recent exploration and development on the platform.